Published February 6, 2025

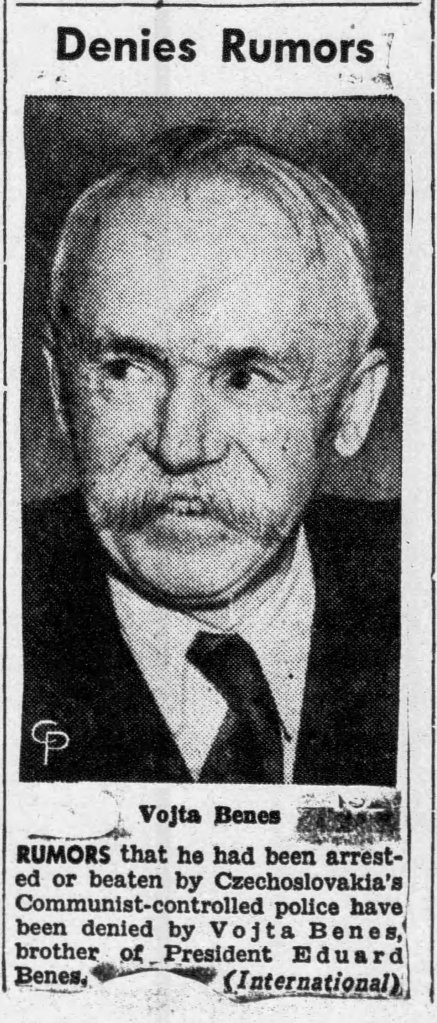

Months back, while sifting through old newspaper articles, I came across something peculiar. It was a small article from the Associated Press in 1950 that mentioned a man named Vojta Beneš living in Mishawaka, Indiana. Beneš was vehemently denying the claims of attempting a coup against the Communist government of Czechoslovakia. The article then mentioned that he was the brother of Edvard Beneš, the former President of Czechoslovakia before the Communist Party took over. Intrigued, I searched for more on Vojta Beneš and discovered that he was not just the brother of a former Czechoslovakian President but was a famous statesman in his own right and was referred to as “Czechoslovakia’s Paul Revere.”

This had me wondering why I had never heard of this man, so I took my findings to the Mishawaka Historical Museum. I presented this evidence to Peter De Kever, the Historian Laureate of Mishawaka, and he had never heard of Vojta Beneš either. I mentioned that another article said that Vojta lived with his with daughter and her husband, Anton Vlcek, whom De Kever did know about. Using information he gave me about Anton Vlcek, I got the first piece needed to solve this puzzle.

Vojta Beneš was born on May 11, 1878, in the Bohemian region of the Austro-Hungarian Empire (modern day Czech Republic). As a young adult, he completed his studies at the Teacher’s Institute of Prague in 1897 and became an instructor at junior high schools. Around this time, he also became fascinated with the concept of his nation’s independence from its imperial rulers. The Czechs for decades were tired of their rulers, as Austria-Hungary mistreated their people, forced them into pointless wars, and taxed them without giving back much in services. They were essentially nothing more than a people conquered by a larger empire. In 1913, Vojta was sent to the United States on a mission to study the American school system and eventually apply the same standard to Austro-Hungarian schools. While in the United States, his dreams of Czech independence grew by learning the history of the United States breaking free from the oppressive rule of the British Empire and getting to meet large communities of Czech people who had previously fled to America from the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Vojta completed his study of American schools in 1914 and came back to his country ten days before the start of World War I. When the war started, and his countrymen were drafted to fight for the Austro-Hungarians and Germans, he knew that the need for Czech independence was now or never. He secretly fled the country to the United States with others and joined the Czech independence movement. This movement that had been slowly growing for years, rapidly expanded due to the onset of World War I. The Czech independence movement needed more support. Vojta and others realized an independent Czech nation would not survive on its own, so their organization joined forces with the Slovakian independence movement. The union between the Czech and Slovak people made the most sense because their regions bordered each other, they spoke similar languages, shared historical ties, and were both ruled and mistreated by the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The name of this new country that both independence movements agreed to was Czechoslovakia.

In the United States, Vojta went to Czech and Slovak communities asking for their support and traveled to Washington, D.C., to lobby politicians to support the creation of Czechoslovakia. The United States government did not give much thought to supporting such a cause despite being sympathetic toward the cries of independence. All that changed, however, when on April 6, 1917, the United States formally entered World War I against the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the German Empire. At that point, the United States started to consider Czechoslovakian independence heavily, and a committee to oversee potential post-war terms was started.

On November 11, 1918, World War I officially ended with the Central Powers, consisting of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the German Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and the Tsardom of Bulgaria, surrendering. Austria-Hungary was no more, and Czechoslovakia became an independent nation. Three days later on November 14, 1918, Tomáš Masaryk was appointed the first President of Czechoslovakia. Vojta and his brother Edvard joined the newly formed government and became allies of Masaryk.

Under the Masaryk Administration, Vojta was tasked with re-organizing the national school system. After he completed the re-organization, he was made the National Director of Czechoslovakian Schools. In 1924, Vojta ran for parliament and won. In 1934, he successfully ran for Senate in western Bohemia. Vojta’s brother, Edvard Beneš, was made Minister of Foreign Affairs in 1918, Prime Minister in 1921, and eventually President in 1935. Due to Vojta’s frequent visits to the United States, his fluent English, public speaking tours across the country, and charisma, he was well-liked by American Czechoslovak communities and Americans alike. His spirit of independence and spreading democracy led to American newspapers giving him the moniker “Czechoslovakia’s Paul Revere.”

In the 1930s, a new existential threat loomed over Czechoslovakia: Nazi Germany, ruled by Adolf Hitler. Hitler started to build up Wehrmacht troops on the border of Czechoslovakia by 1936, which led President Edvard Beneš to start building fortifications on the German border. Hitler then proclaimed that the Sudetenland region of Czechoslovakia belonged to Germany. The Sudetenland was the region of Czechoslovakia where ethnic Germans lived. Despite a majority of ethnic Germans in these regions wanting to stay with Czechoslovakia, Hitler was using it as nothing more than a ploy to take more land to grow the Nazi war machine. Vojta Beneš and other Czechoslovak politicians stood up to Hitler and tried to warn the west that war was on the horizon and that Hitler would not stop with Czechoslovakia.

In 1938, the allies of Czechoslovakia, consisting of the United Kingdom and France, who were fearful of another World War, allowed Nazi Germany to annex the Sudetenland in the Munich Agreement. The Czechoslovakian people referred to this agreement as the “Munich Betrayal.” This mistake by the U.K. and France only strengthened and empowered the Nazis to grow their ambitions of conquering all of Europe. Vojta knew that the end was near for his nation. Despite the Munich Agreement proclaiming that Germany would not take any more of Czechoslovakia, the Germans started putting more troops on their new border. Czechoslovakia was now defenseless, and France and the U.K. turned a blind eye.

In March 1939, the Nazis invaded the remainder of Czechoslovakia. Vojta knew that he had to flee as Nazi Party officials had threatened to hang the Beneš family. He stayed constantly on the move in Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia until June, when at the age of 62 with his 60-year-old wife, Emilie, they grabbed what they could in the night and snuck out to the countryside. They put on trench coats and travelled through the forests, farm fields, and over a river until they successfully crossed the border into Poland without being spotted by the Nazis. In Poland, they were able to get into contact with friends in America and moved back to the United States. Vojta was now in his second exile and was adamant about getting his nation back from the Nazis.

One of the first things that Vojta and Emilie did was go to Chicago to see their daughter Alice, one of their four children, who was going to school there. When World War II started, Vojta helped with the Czechoslovakian government in exile and started raising funds and recruiting political support for resistance movements in his home country. He also urged the United States to resist Germany’s conquest, which came true in December 1941, when the United States formally joined the war. After grueling years of conflict, Europe was freed of Nazi rule in 1945. In May of that year, Czechoslovakia was liberated for a second time, and Vojta and his wife returned once again to rebuild their war-torn nation. Alice Beneš decided to stay in the United States as during the war she got her Bachelor’s of Education in 1941 at the Pestalozzi Froebel Teachers College and a Master’s of Education at the Graduate Teachers College of Winnetka in 1943. While in the United States, Alice also got married to Anton Vlcek, and they had three children, two sons and an infant daughter who passed away after only two days due to health complications. Anton moved the young family from Chicago to Mishawaka in 1948, when he became the director of the Children’s Aid Society (later known as the Family and Children’s Center), located at 1411 Lincoln Way West. After moving to Mishawaka, they became members of the First Presbyterian Church.

As the director of the Children’s Aid Society, Anton became a mentor and a role model for the children growing up at the facility. One of those children was LeRoy Johnson, Mishawaka High School’s most famous basketball legend. LeRoy remembers, “Anton Vlcek played a very important role in my life, and he was a person to whom I could actually talk.” He elaborated with, “He (Anton) could relate to us all, and that certainly was important.” LeRoy also credits his growth in basketball to Anton Vlcek by explaining that Anton had the children do a variety of extracurricular activities and that once LeRoy expressed his love of basketball, Anton gave him all the tools to practice and succeed in the sport. LeRoy also mentioned how caring and loving Alice was to everyone.

While Alice and Anton were establishing a new life in Mishawaka, Vojta was helping his brother Edvard, who was President of Czechoslovakia again. Emilie passed away, leaving Vojta a widower. Vojta, still determined to be a public servant despite all the hardships, ran for and was re-elected to parliament in 1946, with the nation starting to get on track again despite struggling in post-war Europe. All that changed, however, on February 21, 1948, when Communists, backed by the Soviets, launched a coup and took control of the Czechoslovakian government. Edvard was no longer President, and any non-communist, like Vojta, was removed from the government. Edvard Beneš had been in poor health before the coup and passed away mere months after his removal as President of Czechoslovakia. Vojta, though not taken prisoner, was not allowed to leave the country and was heavily monitored for his anti-communist stances.

Pressure was put on Communist Czechoslovakia when Alice (Beneš) Vlcek sent a request asking permission for her father, Vojta, to visit her family. Vaclav Nosek, the Minister of the Interior of Czechoslovakia, initially denied the visit but changed his mind and approved the request, allowing Vojta to leave Czechoslovakia to visit his daughter in February 1949. The stipulation, however, was that the government would freeze all his assets prior to him leaving, resulting in him having no money. Vojta’s visit to Mishawaka became permanent. He had no intention of returning because he had nothing left in Czechoslovakia. He was left penniless but was grateful that he was back with his family. When asked by a reporter why the Communist government let him leave after previously denying him, Vojta said, “They wanted the world to see that they did not hold prisoners in Czechoslovakia.”

While in the United States in his third exile, Vojta helped displaced Czechoslovaks get in contact with services to get them housed and any other needs met. For most of his third exile, he lived in Mishawaka at the Vlcek home on the campus of the Children’s Aid Society. LeRoy Johnson remembers seeing Vojta Beneš often during those two years at the facility. When asked about Vojta, LeRoy said, “He (Vojta) walked with a cane, and I did speak to him numerous times because he would come out of the house, and he was a very friendly man. I remember his moustache; I will always remember that moustache.” LeRoy said that he knew Vojta was Mrs. Vlcek’s father but as a child had no idea of his backstory other than that the Beneš family was important at some point. Vojta was known to walk around the campus often, albeit slowly. LeRoy Johnson may be one of the last people alive to have personally known Vojta Beneš. Vojta was somewhat active in the Mishawaka community, as he gave speeches at different venues. One venue was Mishawaka’s First Methodist Church, where on September 12, 1950, his topic was “The Current Problems Which Face Czechs Today.”

Vojta started slowing down, though, as he began to have health problems. He already was in poor health before moving to the United States, and his condition did not improve. In June 1951, Vojta Beneš suffered a massive stroke. Alice and Anton Vlcek could not care for his growing health problems any longer and put him in a nursing home in South Bend. Vojta Beneš passed away at age 72 on November 20, 1951. He is entombed at the Bohemian National Cemetery in Chicago, Illinois.

Vojta Beneš was a man determined to liberate his people, whether from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Nazi Germany, or Soviet-backed Communists. He was exiled three times and never stopped helping the Czechoslovaks. He improved the education levels of Czechoslovakia and helped passed landmark laws. His educator background inspired two of his children to follow a similar path, as Alice Vlcek was a teacher and his son Vaclav Beneš was a political science professor at Indiana University. Vojta truly earned the title “Czechoslovakia’s Paul Revere” for dedicating his life to public service. Although Vojta Beneš lived in Mishawaka only for most of the last two years of his life, I am proud that our community took in such a remarkable man who was able to live out those years in peace surrounded by his family.

Leave a comment