Published November 21, 2024

The Cold War is a bygone era, with relics of it now becoming a distant memory for those who experienced it. While the concept of a fallout shelter may seem strange today, the rationale at the time was completely justified. The 1960s were a tumultuous time. The Cold War was at its peak with deteriorating relationships between the two superpowers because of events such as the failed Bay of Pigs Invasion, Soviet encroachment on Western Europe like the Berlin Crisis, the Cuban Missile Crisis, and the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. This was also when Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (I.C.B.M.s) were first put into production by both the superpowers. I.C.B.M.s completely changed the scope of war. In prior wars, an invasion or largescale attack on the mainland U.S. seemed improbable, but now the Soviets could launch missiles anywhere in the world that our defensive systems could not stop.

The heightened tensions, and threat of a nuclear attack at any moment caused fear and anxiety in Americans. Cities across the United States needed a plan if such an event were to happen. Mishawaka was one such city that wanted to protect its citizens and be fully prepared. If there was a nuclear war, most Mishawakans wouldn’t survive, as well as hundreds of millions of other Americans. The nuclear bombs would kill people directly or indirectly whether from the initial blasts, the potential nuclear winter, or most importantly from fallout. Fallout is one of the byproducts of a nuclear explosion that is created when dust, ash, and nuclear residue mix high in the atmosphere, then falls down to the earth contaminating wherever the wind carries it. This radioactive debris is deadly to human life, as touching it, breathing it in, or even simply being near it exposes one to toxic levels of radiation.

This is where fallout shelters come in. A fallout shelter is a shelter typically below ground that has thick enough walls to prevent radiation from penetrating and harming the people inside. Depending on the strength and range of the detonation, it also acts as a bomb shelter. Due to the half-life of radioactive elements, the radiation levels are deemed acceptable for human safety two weeks after the detonation of the nuclear bomb. A fallout shelter had everything a family needed to survive those two weeks, such as canned food, water, a toilet, an air pump with filters, and a generator.

The trend of fallout shelters spread across America, including Mishawaka. While Mishawaka was not a direct target for nuclear strikes, declassified documents show that South Bend was a secondary target for the Soviets due to all of the industry and the population. Had South Bend been destroyed by a nuclear explosion, the blast radius would have included parts of Mishawaka, and the fallout would have covered most of St. Joseph County. This proves that it was not hysteria for the craze of fallout shelters here, but rather insurance in the unlikely but possible event of nuclear Armageddon.

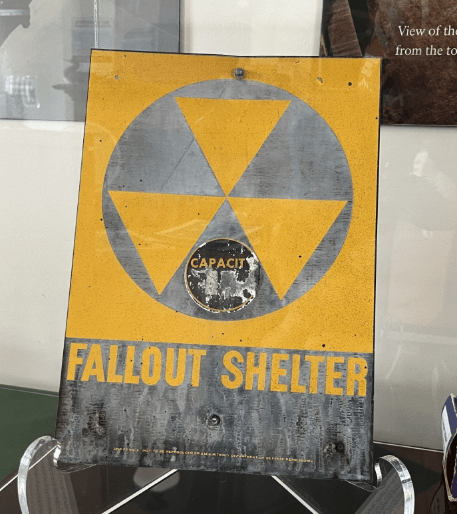

One of the earliest contractors to start building fallout shelters in Mishawaka was Peter Schumacher Sons, Inc., in the fall of 1961. Around this time, the United States Office of Civil Defense (O.C.D.) started to approve of public locations that qualified as fallout shelters. They approved these locations with a black and yellow sign with a modified Trefoil Symbol and the words “FALLOUT SHELTER.” The first two locations in Mishawaka to be approved by the O.C.D. were the Municipal Utilities Building on First Street and Mary Phillips School. By November 1962, 78 locations were approved as public fallout shelters in Mishawaka and South Bend, and they could temporarily hold 55,567 of the 200,000 people in both cities combined.

Some of the approved fallout shelter locations in Mishawaka were the following; St Bavo’s School, Hygrade Meat Plant, Mishawaka Federal Savings, Mishawaka Trust Savings Co., U.S. Rubber Co. Shipping & Receiving Building, First Baptist Church, and the Bethel College Administration Building. Historian Laureate Peter De Kever mentioned that the basement of Mishawaka Federal Savings still had canned food, water, and a Geiger Counter all the way into the 1980s.

While the idea of public fallout shelters was helpful with the masses, they would only moderately protect people from the dangers of radiation, had fewer supplies than needed for those crucial two weeks, and ultimately were not prevalent enough to hold even half the population of the area. Even in the best-case scenario, the living conditions in these public shelters would have been poor. These concerns led to homeowners constructing their own personal fallout shelters or hiring a contractor to do so.

There were two types of personal fallout shelters that were sold to consumers. A 1961 newspaper advertisement from Brugh Engineering Company, 541 Lincoln Way East, South Bend, dealers of ARMCO fallout shelters, perfectly explains the varieties. The first type of shelter was described as follows: “The ARMCO basement shelter utilizes the corner of any home concrete basement. Walls of the shelter are composed of cellular steel panels with a 12-inch void between the steel sheets. This must be filled with sand to provide a shield from radiation. Ceiling is steel, covered with sand.”

The second type of personal fallout shelters sold was “ARMCO’s underground shelter – this shelter offers almost absolute protection against atomic fallout. Includes circular entrance hatch and air cover; air-intake blower; bunk frames.”

These fallout shelters could be partly or entirely covered by a Federal Housing Administration (F.H.A.) loan and could be paid for in small payments. Prices varied due to multiple factors. Another newspaper advertisement for a basement shelter was from Lowe Lumber Company at 328 S. Main Street, Mishawaka, in 1961, which sold one model for $700 dollars ($7,400 in 2024 adjusting for inflation).

Sixty years later, I wonder what has become of all these shelters. For many public shelters, I assume they have been demolished or repurposed for other uses. I wonder if there are homes in the city still with intact fallout shelters that even the homeowners do not know of. While the Cold War has ended and the threat of nuclear annihilation has significantly decreased, I still see the merit of creating and maintaining fallout shelters, as well as teaching the residents of Mishawaka where to go and how to survive the worst-case scenario, no matter how unlikely it is.

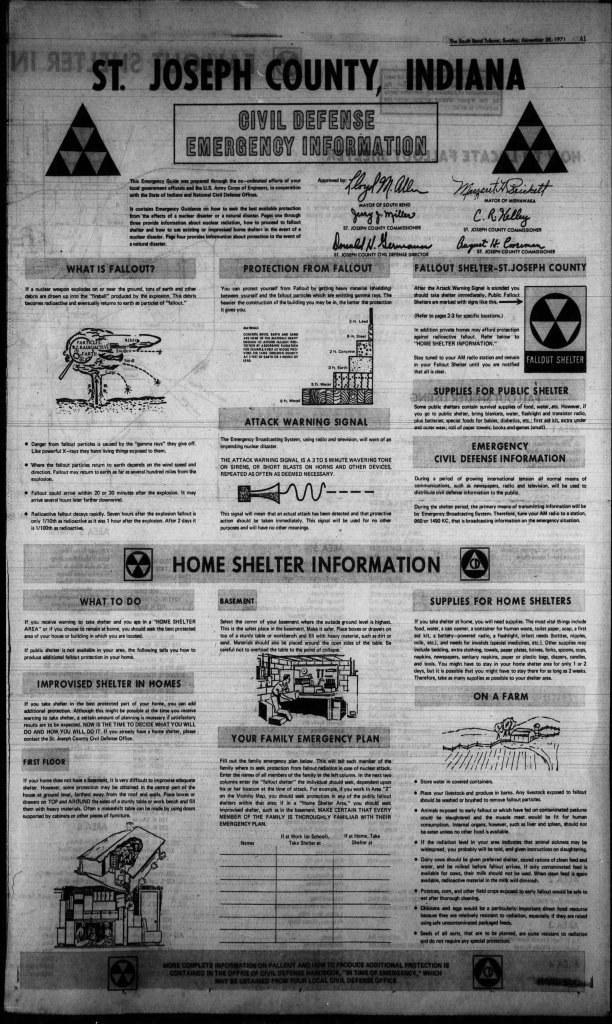

1971 PSA in the South Bend Tribune about what to do in the event of a nuclear war.

Leave a comment